Tax Bracket Conversion Calculator

Optimize Your Roth Conversions

Calculate how much you can convert to Roth IRA while staying within your tax brackets and avoiding Medicare surcharges.

Your Tax Bracket Analysis

Recommended Conversion

Optimal Conversion Amount: $0

Estimated Tax Due: $0

Long-Term Benefit

By converting $0, you'll pay $0 in taxes now but save $0 in future taxes.

Your tax-free growth will increase by $0 over time.

Most people think taxes in retirement are just something you deal with-bigger withdrawals, higher bills, and no way out. But what if you could pay less tax now, lock in today’s rates, and let your money grow completely tax-free for the rest of your life? That’s not a fantasy. It’s tax bracket management through Roth IRA conversions-and it’s working for thousands of Americans right now.

What Exactly Is a Roth Conversion?

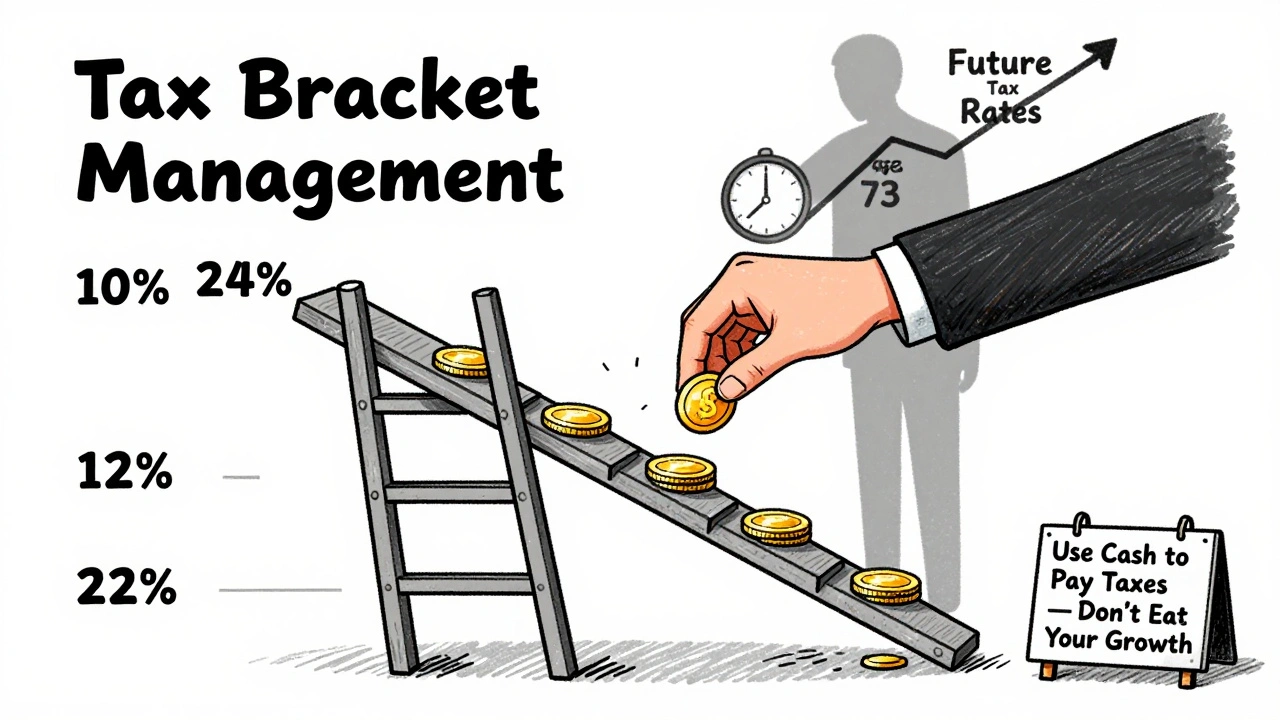

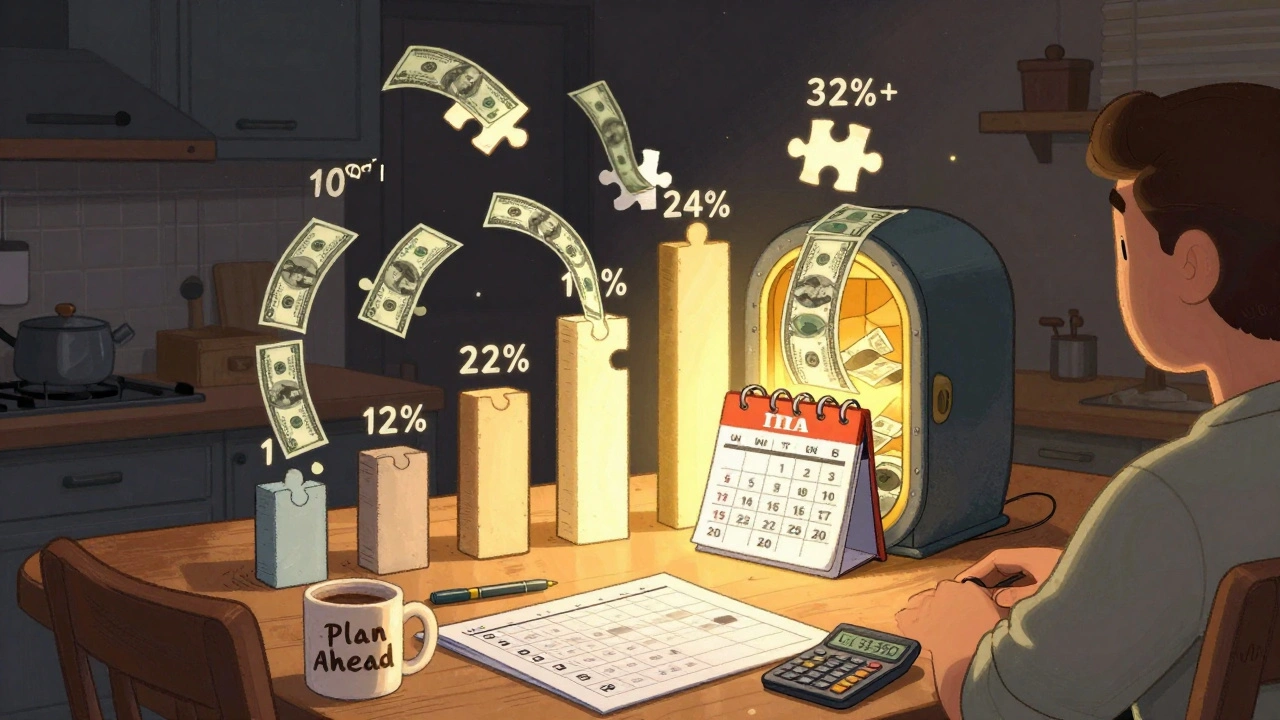

A Roth conversion means moving money from a traditional IRA or 401(k) into a Roth IRA. Sounds simple, right? But here’s the catch: you pay income tax on the amount you convert. That’s the price of entry. In return, you get tax-free growth and tax-free withdrawals later. No more taxes when you take money out in retirement. No required minimum distributions (RMDs) that force you to withdraw and pay taxes whether you need the money or not. The real magic isn’t in the conversion itself-it’s in when you do it. The goal isn’t to convert when you’re earning $400,000 a year. That’s when you’d pay 32% or 35% in federal taxes. The goal is to convert when your income is low-during a gap year between jobs, after retiring but before taking Social Security, or even during a year you took a pay cut. That’s when you can fill up the lower tax brackets-10%, 12%, 22%, even 24%-and pay way less than you will later.How the 2025 Tax Brackets Work (And Why They Matter)

For 2025, the federal tax brackets for single filers are:- 10% on income up to $11,925

- 12% on income from $11,926 to $48,475

- 22% on income from $48,476 to $103,350

- 24% on income from $103,351 to $197,300

- 32% on income from $197,301 to $250,525

- 35% on income from $250,526 to $626,350

- 37% on income above $626,350

- 10% on income up to $23,850

- 12% on income from $23,851 to $96,950

- 22% on income from $96,951 to $206,700

- 24% on income from $206,701 to $394,600

- 32% on income from $394,601 to $454,100

- 35% on income from $454,101 to $751,600

- 37% on income above $751,600

When Is the Best Time to Do a Roth Conversion?

The sweet spot? Between ages 55 and 70. That’s the gap between when you retire and when you have to start taking RMDs from your traditional retirement accounts at age 73. During those years, your income often drops-no paycheck, no bonuses, maybe just part-time work or rental income. That’s your chance to fill the lower brackets. Another common window is after a big expense. Maybe you sold a business, took a year off to care for a family member, or moved to a lower-cost area. Your income dips. That’s not a setback-it’s an opportunity. One doctor I know retired at 58. His pension and rental income put him at $95,000 in taxable income. He had $1.2 million in a traditional 401(k). He converted $50,000 a year for five years. Each year, he stayed under $103,350-the top of the 22% bracket. He paid about $11,000 in taxes per year. By the time he turned 73, he’d converted $250,000. That $250,000 is now growing tax-free. When he starts taking RMDs from the rest of his account, his taxable income stays lower because he already moved half of it out. His Medicare premiums? Lower. His tax bill? Smaller. His peace of mind? Huge.

What Happens If You Convert Too Much?

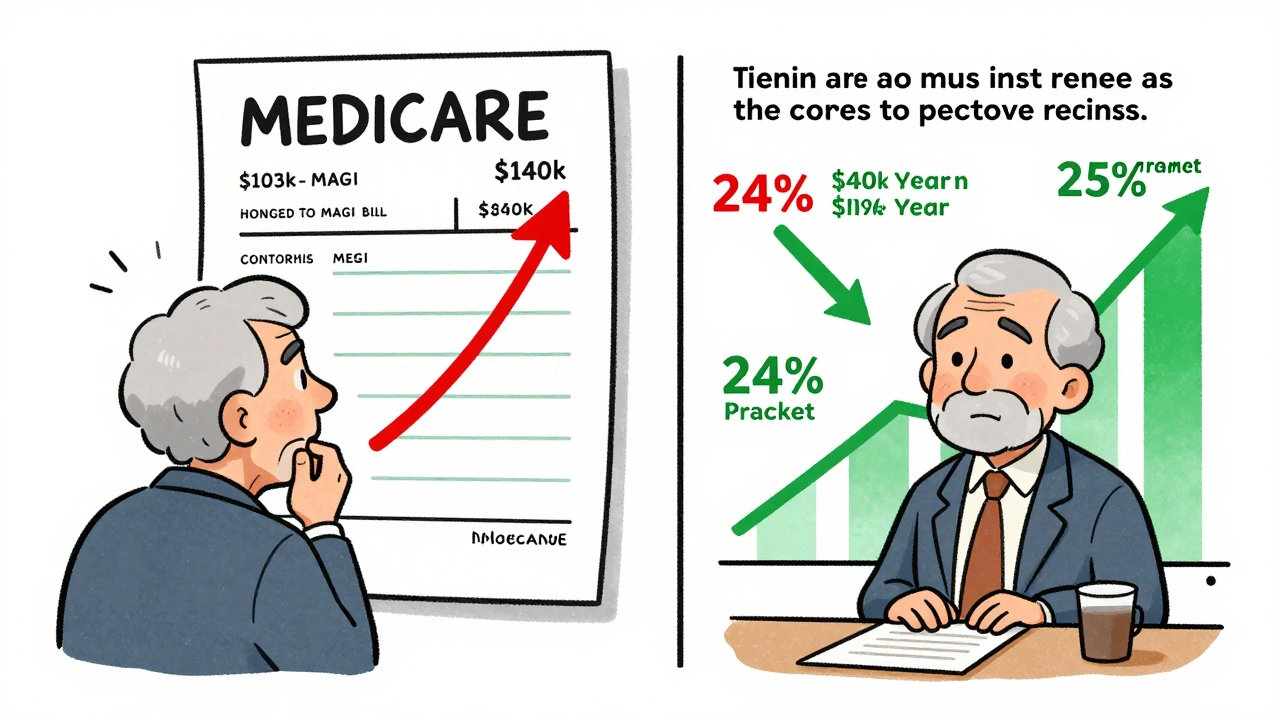

This is where most people mess up. Converting too much doesn’t just mean paying more tax-it can trigger other costs you didn’t expect. First, Medicare. If your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) goes above $103,000 (single) or $206,000 (married), you pay higher Medicare Part B and D premiums. These aren’t small. They can add $100-$400 extra per month. So if you convert $80,000 in one year and your income jumps to $140,000, you’re not just paying 24% tax-you’re paying more for healthcare too. Second, the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). If your MAGI exceeds $200,000 (single) or $250,000 (married), you pay an extra 3.8% tax on investment income. Roth conversions count toward MAGI. So if you’re already near that line, a big conversion could push you into this tax too. Third, state taxes. If you live in California, New York, or Minnesota, you’ll pay state income tax on your conversion too. California’s top rate is 12.3%. So a $50,000 conversion could cost you $12,000 in federal tax and $6,150 in state tax-$18,150 total. That’s a lot to pay upfront. The rule? Don’t convert more than you can afford to pay taxes on-with cash you didn’t take from the IRA. If you use the converted money to pay the tax, you’re eating into your tax-free growth. That defeats the whole point.How Much Should You Convert?

Start by calculating your current taxable income. Then, subtract that from the top of the next bracket. The difference is your conversion room. Example: You’re married, filing jointly. Your taxable income this year is $280,000. The 24% bracket ends at $394,600. So you have $114,600 of room before hitting 32%. You could convert up to $114,600-but you shouldn’t. Why? Because you’re already close to the 3.8% NIIT threshold of $250,000. You’re already paying it. So converting more will only raise your MAGI further and could push you into higher Medicare premiums. Better move: Convert $40,000 this year, $40,000 next year, and $34,600 the year after. That fills the 24% bracket without triggering extra taxes. Spread it out. Let your income breathe. Schwab’s research shows people who spread conversions over 3.2 years on average get 18.7% better after-tax results than those who do one big conversion. Patience pays.Roth Conversions vs. Other Strategies

Some people ask: Why not just keep contributing to a traditional 401(k)? That lowers your taxable income now. But here’s the trade-off: you’re deferring taxes, not avoiding them. When you withdraw in retirement, you’ll pay your then-current rate-probably higher. Compare that to a Roth conversion. You pay tax now at 22%. Later, you withdraw tax-free. If your rate jumps to 28% in retirement? You win. If it drops to 12%? You lose. But most people don’t drop-they rise. Inflation, rising healthcare costs, and Social Security taxation push incomes higher in retirement. Tax loss harvesting? Great for offsetting capital gains, but you can only use $3,000 a year to reduce ordinary income. Not enough to move the needle on a $100,000 conversion. Bunching deductions? Useful if you’re near the standard deduction, but it only gives you a one-year tax break. Roth conversions give you a lifetime benefit. The bottom line: Roth conversions are the only strategy that lets you lock in today’s rates and turn taxable money into tax-free money. No other tool does that.

What You Need to Know Before You Start

- You can’t undo it. Since 2018, the IRS no longer allows recharacterizations. Once you convert, it’s final.

- Use cash to pay the tax. Don’t take money from the IRA to cover the tax bill. That reduces your long-term growth.

- Track your basis. If you’ve made non-deductible contributions to your traditional IRA, you need Form 8606 to avoid double taxation.

- Watch state taxes. California, New Jersey, Minnesota, and others tax conversions. Factor that in.

- Don’t ignore RMDs. If you’re over 73, you must take your RMD first before converting anything else.

Is This Strategy Right for You?

Ask yourself these three questions:- Do you expect to be in the same or higher tax bracket in retirement? If yes, this strategy helps.

- Do you have cash on hand to pay the taxes without touching your retirement account? If yes, you’re ready.

- Are you between 55 and 70, or in a year with unusually low income? If yes, this is your window.

What Comes Next?

Start with your tax return from last year. Find your taxable income. Look at the 2025 brackets. Calculate how much room you have in the 22% or 24% bracket. Then, talk to a CPA who understands Roth conversions-not just a generic tax preparer. This isn’t DIY. A small mistake can cost you thousands. And don’t wait until December. The earlier you plan, the more control you have. You can do partial conversions all year long. Many brokers let you convert $5,000 in March, another $10,000 in August, and the rest in November. That way, you can adjust based on your actual income and avoid surprises. This isn’t about avoiding taxes. It’s about choosing when to pay them. And right now, the lower brackets are wide open. Fill them while you can.Can I do a Roth conversion if I’m over 70?

Yes, you can. But you must first take your Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) for the year. Only after that can you convert additional funds from your traditional IRA to a Roth. The RMD itself cannot be converted-it must be withdrawn and taxed as income. Converting after taking your RMD still lets you reduce future RMDs and avoid higher tax brackets later.

Do Roth conversions affect Social Security taxes?

Yes. Roth conversions increase your Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), which determines how much of your Social Security benefits are taxable. If your MAGI crosses the $34,000 (single) or $44,000 (married) threshold, up to 85% of your benefits become taxable. That’s why many people delay conversions until after they start receiving Social Security, to avoid pushing themselves into higher taxation on both income and benefits.

Is it better to convert all at once or over several years?

Spreading conversions over multiple years almost always works better. Doing one large conversion can push you into a higher tax bracket, trigger Medicare surcharges, or bump you into the Net Investment Income Tax. Spreading it out lets you stay in lower brackets, avoid penalties, and reduce overall tax liability. Research shows taxpayers who spread conversions over 3.2 years on average see 18.7% better after-tax outcomes than those who convert everything in one year.

Can I convert only part of my traditional IRA?

Absolutely. You don’t have to convert your entire account. You can convert $10,000 one year, $15,000 the next, or even $2,000 if that’s all you need to fill the 12% bracket. This flexibility is one of the biggest advantages of Roth conversions-you control the timing and amount.

What if tax rates go up after I convert?

If tax rates rise after you convert, you win. You already paid tax at the lower rate. Your Roth account grows tax-free, and future withdrawals are completely tax-free, regardless of what the rates are then. That’s the whole point of the strategy: locking in today’s lower rates before they potentially rise. Most tax professionals expect rates to increase after 2025, making Roth conversions even more valuable.

Do Roth conversions count toward the annual IRA contribution limit?

No. Roth conversions are separate from annual contribution limits. In 2025, you can contribute up to $7,000 to an IRA ($8,000 if you’re 50+), and you can also convert any amount from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA regardless of your income or contribution limits. The conversion doesn’t use up your contribution room.

Comments (4)

Julia Czinna

This is one of those posts that makes you stop and actually think about retirement planning differently. I did a partial Roth conversion last year after my husband took a sabbatical, and it was the smartest financial move we made in five years. We stayed under the 22% bracket, paid about $8k in taxes, and now that $65k is growing tax-free. No more panic in December when the IRS letter arrives.

Also, using cash to pay the tax? Non-negotiable. I saw someone try to use IRA funds to cover the bill once - they ended up with less growth and a bigger penalty. Don’t be that person.

And yes, spreading it out over years is the real hack. I did $15k/year for four years. Felt like stealing from the future税务局.

Astha Mishra

It is truly fascinating how the structure of taxation in the United States, though seemingly rigid and bureaucratic, can be navigated with such elegance when one possesses not only knowledge but also patience and foresight. The concept of filling lower tax brackets through strategic Roth conversions is not merely a financial maneuver-it is a philosophical act of aligning one’s present sacrifices with future freedom.

Consider this: we live in an age where instant gratification is glorified, yet here we are, choosing delayed reward over immediate ease. To convert now, to pay taxes today when income is low, is to reject the cultural conditioning that equates wealth with consumption. It is to say: I will endure discomfort now so that my later self may breathe without the weight of the IRS on their chest.

And yet, many do not even realize they have this choice. They assume taxes in retirement are inevitable, like aging or gravity. But they are not. They are a policy, a variable, a lever. And those who pull it wisely-those who calculate, plan, and wait-are not just wealthy. They are free.

Perhaps this is the quiet revolution: not in protests or politics, but in spreadsheets and tax forms. A revolution of dignity, one Roth conversion at a time.

Dave McPherson

Oh wow. Another ‘Roth conversion guru’ post. Congrats, you just wrote a 3,000-word ad for a CPA who charges $500/hour to tell you what you could’ve googled in 10 minutes.

Let me guess-you’re the guy who’s still using Excel to track your IRA basis because you think ‘tax software is for plebs.’

And let’s not forget the classic: ‘Don’t use IRA money to pay taxes!’ Bro, if you’re converting $50k and you don’t have $12k in cash lying around, you probably shouldn’t be investing in IRAs in the first place. You’re not a financial wizard-you’re just someone who got lucky with a 401(k) and now thinks you’re Warren Buffett with a TurboTax subscription.

Also, ‘spread it over 3.2 years’? That’s not a strategy, that’s a math problem for a middle schooler. And don’t even get me started on the Medicare premium FUD. If you’re that close to the threshold, you’re already in the 32% bracket. Your ‘low-income gap year’ is a myth. You’re not ‘filling brackets’-you’re trying to look smart on Reddit.

RAHUL KUSHWAHA

This is gold. 😊 I did this last year after my contract ended. Only converted $8k to stay in 12%. Paid $960 tax. Now it’s growing free. No stress. 👌