Secondary Offering Impact Calculator

Estimate Stock Price Impact

Enter values to see estimated impact

When a company goes public, it sells shares for the first time in an IPO. But that’s not the end of the story. After the IPO, companies and early investors often come back to the market with something called a secondary offering. It sounds simple - just selling more shares - but what happens next can make or break a stock’s price. Understanding how these offerings work, and why they move prices, is critical for any investor holding shares in a public company.

What Exactly Is a Secondary Offering?

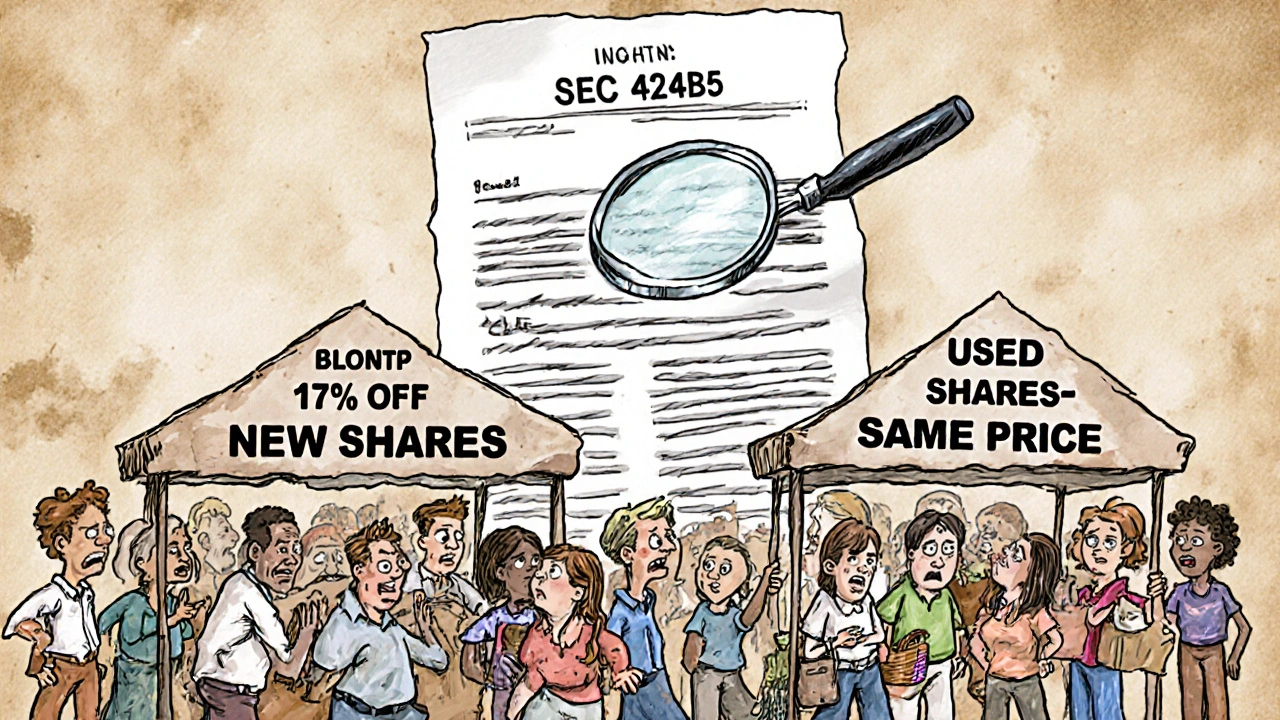

A secondary offering is when shares are sold after a company’s IPO. But not all secondary offerings are the same. There are two main types, and they have opposite effects on your ownership and the company’s finances. The first type is a non-dilutive secondary offering. This happens when existing shareholders - like venture capitalists, founders, or early employees - sell their shares to the public. The company doesn’t get any money. The cash goes straight to the sellers. Think of it like someone selling their used car: the car’s value doesn’t change just because it changed hands. The second type is a dilutive secondary offering, also called a follow-on offering. Here, the company itself issues new shares. More shares mean more total ownership out there. That’s dilution. Your 1% stake might drop to 0.95% overnight. The company gets the cash, though - usually to pay down debt, buy another business, or fund new projects. These aren’t just academic distinctions. They determine whether your shares become more or less valuable after the announcement.How Do Secondary Offerings Affect Stock Prices?

Stock prices don’t react to the idea of a secondary offering - they react to what kind it is and how it’s handled. Dilutive offerings almost always cause a price drop. Why? Because earnings per share (EPS) gets split across more shares. If a company made $100 million in profit and had 100 million shares, EPS was $1.00. If it issues 20 million new shares, EPS drops to $0.83 - even if profits stay the same. Investors notice this. Data from Goldman Sachs shows dilutive offerings cause an average 4.2% price drop on the day of announcement. Non-dilutive offerings are trickier. The company doesn’t get new money, but the stock still often falls - just less. On average, these cause a 1.8% dip. Why? Because the market sees more shares suddenly available. More supply means lower prices, unless demand is strong enough to absorb it. Timing matters too. About 68% of secondary offerings happen within 180 days after an IPO lock-up expires. That’s when early investors are finally allowed to sell. If a bunch of them dump shares all at once, the price can tumble. But if the selling is spread out, or if the market expects it, the drop can be mild.Why Do Companies Do This?

Companies use dilutive offerings to raise capital without taking on debt. Tesla raised $5 billion in 2020 through a follow-on offering to build Gigafactories. Amazon did the same in 1998 to fund international growth. In both cases, the money went into high-return projects. The stock price dropped at first - but then surged as the businesses grew. Non-dilutive offerings serve a different purpose: liquidity. Early investors like Sequoia Capital didn’t want to hold Coinbase forever. They sold chunks of their stake over time through non-dilutive offerings. The company didn’t get cash, but the investors did. And since no new shares were created, the company’s financials stayed clean. Sometimes, it’s a mix. A company might sell shares to raise cash (dilutive) while insiders simultaneously sell some of their own (non-dilutive). That’s when confusion sets in. Investors have to ask: Is the company raising money to grow - or are insiders bailing?

What Investors Should Watch For

Not all secondary offerings are bad. Some are outright bullish. Here’s how to tell the difference. First, check the discount. Dilutive offerings are usually priced 3-7% below the current market price to attract buyers. If the discount is 10% or more, that’s a red flag. It suggests the company knows the stock is overvalued - or demand is weak. Second, look at who’s selling. If it’s a founder or CEO selling shares, that’s a signal. If it’s a hedge fund that’s held the stock for five years, it’s probably just taking profits. Check SEC Form 4 filings to see who’s selling and how much. Third, watch the volume. If the offering size is more than 200% of the stock’s average daily trading volume, the market may struggle to absorb it. That’s when you see long-lasting price drops. If the offering is small relative to trading volume - say, 50% or less - the impact is often minimal. Fourth, read the purpose. If the company says it’s using the cash to pay off debt or buy a competitor, that’s a good sign. If the filing says “general corporate purposes,” that’s vague. It could mean anything - including covering losses.Real-World Examples That Tell the Story

In April 2023, Rivian raised $1.6 billion through a dilutive offering. The stock dropped just 1.2% the next day. Why? Because investors knew the money was going toward new vehicle launches. The market trusted the plan. Contrast that with WeWork’s 2021 offering. The company had already lost billions. Investors didn’t believe in the business model. The offering was priced at a 17% discount. The stock collapsed. On the non-dilutive side, Pinterest’s 2022 offering sparked outrage on Reddit. Users called it a “sell-off by insiders.” The stock fell 18% in a week. But Fortinet’s 2023 offering was met with cheers. The company had strong earnings, and the offering was small. The stock kept rising. The market absorbed the shares quickly.

How to React When a Secondary Offering Is Announced

Don’t panic. Don’t rush to sell. Do this instead:- Wait 3-5 days after the announcement. Most of the price drop happens in the first 48 hours.

- Check if the offering is dilutive or non-dilutive. Use the company’s SEC filing (Form 424B5).

- Recalculate EPS if it’s dilutive. Divide current earnings by the new total number of shares.

- Compare the offering size to average daily volume. If it’s under 150%, it’s manageable.

- Look at the company’s fundamentals. Strong revenue growth? Healthy balance sheet? The stock will likely recover.

Comments (4)

Astha Mishra

It's fascinating how secondary offerings reveal so much about a company's soul, not just its balance sheet. When a founder sells shares, it's not merely a financial transaction-it's a silent confession of faith, or lack thereof. And yet, we often reduce this to a spreadsheet calculation: EPS down, price down. But what if the real question isn't whether the stock will recover, but whether the company still believes in its own future? The market may punish ambiguity, but it's the human element-the quiet confidence of a CEO reinvesting in R&D while insiders exit-that tells the true story. I've watched companies like Tesla and Amazon endure brutal dilution, only to rise not because of accounting magic, but because they kept building things people needed. Maybe the real indicator isn't the discount or the volume, but whether the leadership still has skin in the game after the offering. That’s the kind of depth we rarely discuss in forums like this.

Kenny McMiller

Bro, dilutive = bad, non-dilutive = maybe bad but less bad. That’s the TL;DR. But seriously, if you’re seeing a 10%+ discount on a follow-on, that’s the market screaming ‘this company is overvalued’. And ATM offerings? Absolute torture for long-term holders. It’s like your rent goes up $10 every week and the landlord says ‘it’s just a small drip’. Moderna did that and now my position’s down 40% even though the vaccine worked. The SEC needs to force companies to label these like food labels: ‘DILUTION ALERT: 12% ownership erosion over 18 months’. Investors aren’t dumb-we just get tired of being fed bullshit with ‘general corporate purposes’ as the excuse. If you’re not buying a factory or a patent, you’re just buying time to avoid bankruptcy.

RAHUL KUSHWAHA

Thanks for this. Really helpful breakdown. I’ve been confused about why Pinterest dropped so much after their offering-now I see it was insiders selling. 😔

Julia Czinna

One thing people overlook is the psychological impact of timing. A secondary offering right after earnings season, when optimism is high, gets a much gentler reception than one right after a product flop. The market isn’t just pricing in dilution-it’s pricing in narrative. If a company announces a $500M offering the day after missing guidance, it’s not about the shares-it’s about trust. That’s why Rivian’s 1.2% drop was so telling: investors believed the plan. We don’t react to numbers. We react to stories. And right now, the story of EVs is wearing thin. So unless the offering comes with a new narrative-like a breakthrough battery or a partnership with a major automaker-it’s just noise. Read the filing. Then read between the lines. That’s where the truth hides.